NINA GHANBARZADEH & ETHAN KRAUSE • CONVERSATIONS

June 16 – July 26, 2018

Milwaukee artists Nina Ghanbarzadeh and Ethan Krause have drawn inspiration from each other’s printmaking processes for an exploration of translations and truth that will be on display this summer in the Wilson Center’s Ploch Art Gallery. Situating text as a place for shifting perspectives in her art, Ghanbarzadeh examines what happens to communication when written text steps out of its traditional function, while Krause’s half-tone screen images highlight the incompleteness and permeability of our knowledge base.

ARTIST STATEMENTS

NINA GHANBARZADEH

Nina Ghanbarzadeh who lives between two cultures (American-Persian) finds herself translating constantly. She tries to avoid this by situating text as a place for shifting perspectives in her art. Would it be possible to communicate without being concerned with legibility or translation? How communication gets affected when written text steps out of its traditional function? Would the art have the same impact if the original language were to be translated? Is it even necessary to translate when text acts as color or shapes in work of art? What happens when written text is being treated as an object? Ghanbarzadeh writes repetitive lines of text that unfold into pattern and shapes. These shapes have entities of their own that respond to the written text or phrase and also reveal some cultural or personal information. She is inspired by Persian poetry and memories of her birthplace. Her repetitive lines of phrases depict her emotions at a specific moment of time. Through the meditative act of writing repetitively and creating shapes, she is trying to explore her multicultural life and background.

ETHAN KRAUSE

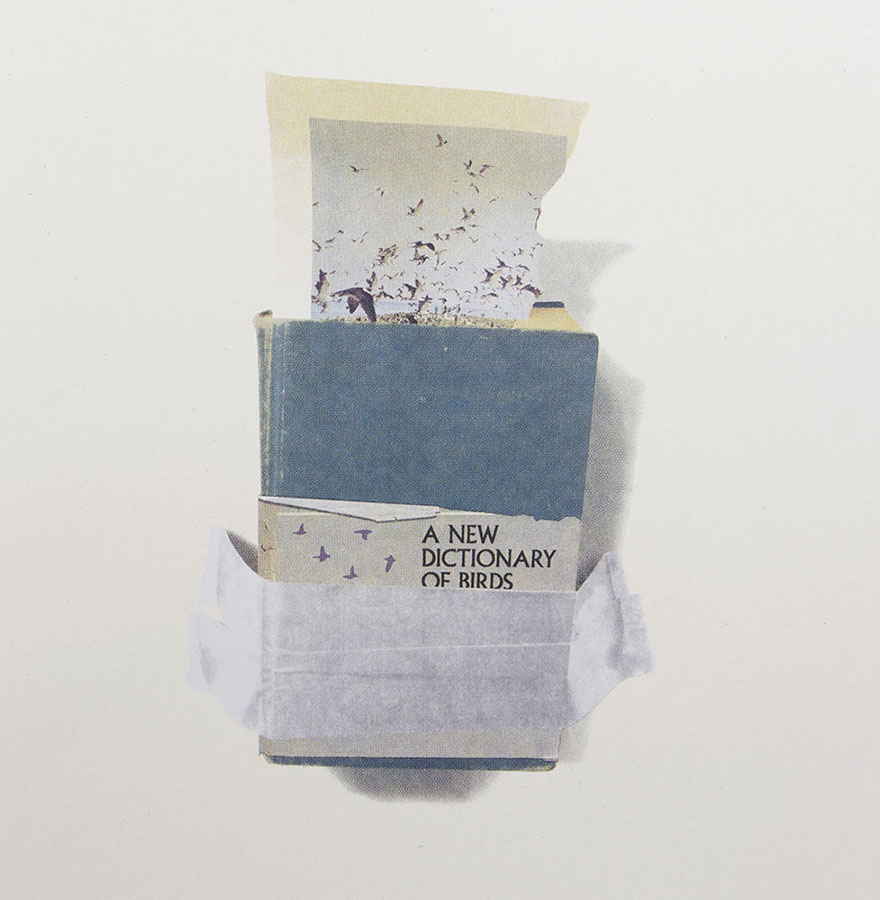

In "The Library of Babel," Jorge Luis Borges posits a library as infinitely complex as the universe. Libraries, with books alpha-numerically ordered on rows of shelves, suggest neat consensus and completeness, but as no physical library can replicate Borges' philosophical construct, a library is an ongoing, open conversation. Appropriately enough, the first two English language translations of "The Library of Babel" appeared almost simultaneously–real libraries are spaces of debate and possibility. Published since 1884, the Oxford English dictionary recently declared "post-truth" to be the international word of the year for 2016. Registering the weird irony that this vaunted compendium of knowledge should officially acknowledge the irrelevance of objectivity in public discourse, my most recent screen prints on paper are an interrogation of material culled from books and printed ephemera. These prints are not a validation of Trumpian, post-truth society but model an active engagement with arguments past and present. I aspire to make compositions that are stately but awkward, the arrangements of images suggestive of something temporary, tenuous, ready to come apart or be rearranged. The many halftone screens that comprise these images break down under closer scrutiny. The commercial printing of the source material confers a veneer of truth, like the order of a library, but the repurposing and recombination highlights the incompleteness and permeability of our knowledge base. The slight imperfections in registration that are a byproduct of hand-printing point to the flaws and gaps in any text or document. My prints are an attempt to enter into dialog with print culture, scanning and photographing old material, arranging and rearranging it on a computer screen and returning it to print through another screen, the mesh of a silk screen. I hope we will never be post-truth as long as the search for knowledge is viewed as an ongoing process, an ever open conversation stretching through time.

ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES

NINA GHANBARZADEH was born and raised in Tehran, Iran. She obtained her Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry from Pune University, India in 1989. She immigrated to the United States in 2001 and received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee with a focus in fine art and graphic design in 2013. She recently completed two years in RedLine Milwaukee’s artist in residency program. RedLine is an urban arts laboratory that seeks to nourish the individual practice of contemporary art and also provide access to art to diverse communities. She is also part of Material Studios and Gallery in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Ghanbarzadeh has participated in a number of group shows in Wisconsin. She is the recipient of Mary L. Nohl Suitcase Export Fund, Student Silver ADDY and Fredric R. Layton Foundations Scholarship Awards. She is also a teaching artist and has been involved in many workshops, lectures, and presentations. www.ninaghanbarzadeh.com | CV

ETHAN KRAUSE is a Milwaukee-based printmaker and book artist. He received his BFA in painting and drawing in 2006 and is a recent MFA graduate in print and narrative forms from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Since 2009, he has published fifteen zines through his imprint Lemon o Books, including eight volumes documenting the participatory mail art project The Famous Hairdos of Popular Music. www.ethanthomaskrause.com

ARTIST INTERVIEW

Inspiration (Backstory)

The following questions are intended to provide insight into the artist's process, how they got started and what inspires them.

Was there a person or event that got you started creating your art? Does that person or event continue to influence the work that you do?

NG: No there was not any person or event that got me started. But when I was a student at UWM, my daughter had been a big inspiration for many of the ideas behind my works. I often ask her opinion on what I make.

EK: In 1992, when I was eight or nine years old, my dad got a giant copy machine for his home office, and I immediately started using it to photocopy my drawings. They were just ballpoint pen drawings I was copying, making them smaller or larger, and it wasn't until decades later, when I was an adult, that I realized how early I'd been set on the path to becoming a printmaker. I'm still trying to figure out what's so compelling about seeing an image reproduced, all the meaning that can be wrung out of these processes. The history of print is so rich and varied, from fine art to books to bus transfers, and maybe that's what makes it so inviting and welcoming, that a kid can unwittingly find himself making prints on a copy machine in the basement.

At what point did you consider yourself an artist?

NG: I was in the fifth grade that I realized how much I loved making art. I was too young then to decide if I wanted to be an artist or not. I just knew that I enjoyed making drawings and paintings. It wasn't after I graduated from high school that I decided to become an artist. But unfortunately I never had the opportunity to attend an art school. Instead I got a bachelor's degree in chemistry, but I never pursued it as my career.

EK: I think I finally considered myself an artist when I started selling and trading zines at festivals around the Midwest and mailing them around the globe. Zines are small, handmade books, and they can really be anything. They're cheap to make, but no one gets rich making them. You make something you want to see in the world, and people who read and make zines–they're often one and the same–understand the love and dedication that goes into them. It was a very welcoming community, and I was able to see myself as an artist in relation to this diverse community of people I considered artists as well.

Who or what inspires you and why?

NG: As I explained in question number one, my daughter was a big influence on my earlier works. The mother-in-me would make art at that time! But generally speaking, I get inspired by listening to music, looking at magazines or photographs. I often find ideas in the least expected places. Once I was attending one of the lecture series at UWM, which is on Wednesday evenings. The guest speaker was from the Netherlands and had a thick accent. As I was listening to her, I started thinking about my own challenges switching in between Farsi (my mother tongue) and English and trying to speak correctly. Then suddenly an idea sparked in my head and I immediately made a quick sketch and later worked on it in my studio. It was a well received drawing.

EK: Really broadly, I'm inspired by books and printed matter, the stuff and ideas around me. I always start working as a sort of conversation. Sometimes, I'm trying to process a text I'm reading, thinking about nature writers like Rachel Carson or Aldo Leopold, performing a kind of seance, trying to figure out what lessons they can still teach in the 21st century. Other times, current events feel much more pressing, but of course it's all connected. Our relationship to nature is a recurring thread, examining and critiquing the human drive to control, the hubris that often characterizes our movements on this planet. The earth seems limitless, but like our own lives, is fragile and finite. Our big brains are our best asset and greatest liability, and I hope my work points to better, less selfish ways of being.

What was the first piece of art you made? Do you remember why you made it? What materials did you use and why?

NG: I don’t remember what was my first art. I remember making a lot of crafts when I was younger. I did a lot of knitting, sewing, bead works, paper crafts but I would not call them art. Why I made them? I liked making things for myself and others. I remember enjoying designing and purchasing materials for my crafts.

EK: When I was very young, I wasn't precious about the art I made, so I made lots of it–stacks and stacks of drawings, never fancy. I think that's why books and works in series are still exciting to me, because no one image needs to have all the answers. You can go back and edit the mess later. One page or one picture is just part of a conversation.

Are there any programs or learning opportunities that you wish you had as a young artist?

NG: Yes. I wish that I would have taken some English and writing classes. I had no clue that good writing is crucial to the art practice. I would also take more photography and philosophy classes.

EK: The art programs and classes I attended when I was young were very focused on learning skills–teaching you to be a better drawer or painter or whatever. I wish I had found something more focused on fostering community and collaboration. The concept that you first need to learn a set of skills and then you can use them to express ideas is sort of strange and old-fashioned, I realize now. The ideas can totally come first.

What would you say to a young person to encourage their study and practice of art?

NG: Have regular studio hours and keep on making art. Never get rid of your early works. Make an archive of the art that you make regardless of their flaws or mistakes.

EK: If I could give one piece of advice to a young person who's excited about art, I would tell them to look for opportunities to share their work and their practice. They make art because it makes them happy, but you never know what it can do until you extend it beyond yourself. Share it online, make copies of it, give it away. Talk to people. Sign up for classes and workshops and look for ways to collaborate. This is good advice for anyone, myself included.

Artistic Practice

The following questions are intended to create insight into the artist’s practice and why they think art is important.

Is this your first and only career? If not, what other jobs have you had and how have they influenced your artistic practice?

NG: I am a full time visual artist and it is my only career.

EK: Art-making is definitely not my first and is still not my only career. I've been a baker and a cook longer than anything else, but I see a lot of parallels between making food and making prints. In both, there's a balance you need to find between carefully following a set of steps and chasing more spontaneous ideas. In both cases, for it to work, you have to enjoy doing both. Sometimes, I find, you do need to measure twice and cut once, as the saying goes. Sometimes, you just go for it.

Do you like people to see your work/comment on it while it is still in process? Why?

NG: I've always welcomed any comments because I believe that art without viewers and discussions is not complete and meaningful. Although commenting on my drawings while they are in the process of making is kind of not easy but on many occasions people and other artists looked at the in-progress works and commented on them. I think that it is the job of the artists to filter the comments and extract what could challenge them upon improving their art. I also never discard the negative comments. I find them more interesting than the positive ones.

EK: Honestly, I'm a little bit secretive while I'm working. There's a vulnerability in sharing work that's not resolved. I would like to explore more collaborative projects in the future, though, and I'd need to let that fear go.

Do you have a daily artistic ritual or routine? If so, how does this help you?

NG: My routine starts with responding to the emails, updating the social media (I don't spend a lot of time on them, I only post any art related news). I like to look at the art related headlines and read articles that interests me. Then I continue working on the in progress pieces. I prefer to make drawings in the day light and do the paper works and writings at the end of the day. I also update my website regularly and document my new pieces as soon as they get completed. This routine helps me to be organized at all times and be prepared for any possible opportunity and submissions.

EK: If I'm not working a big project or print, I'm reading and looking and plotting. I do very little sketching. I find that most of my really good ideas happen in the making, when a plan changes and new decisions surprise me. The reality of ink on paper bumps into whatever I thought it would do in my mind.

What inspiration/research led you to your current body of work?

NG: I've been using the idea of "text as image" in art making while I was still a student at UWM. But this idea started to grow and expand with a questionnaire that I'd prepared in 2013. It was ten questions that had been emailed to Iranians who have been living outside Iran for more than ten years. The responses were then collected anonymously. One of the questions was:"What comes to your mind when you think about your birth place?". Some of the responses were not accurate name of colors like color of the mountains. I had to find a color to substitute that and also stay true to the actual responses. I then made a list of the colors and pinned it on my studio wall. I knew that I wanted to use those colors somehow in my art but I didn't know how. They were not a pretty color palette really but I could write them in my language and this way stay as true as possible to the collected responses! I made a small composition just by writing the name of the colors and I really liked what I saw. That was the starting point for me to research more on Farsi (official language in Iran) and push the idea of using written text in art making. This also has led me to take several directions and expand upon my body of work.

EK: The history of still life painting, especially Dutch Baroque still life, has been a steady source of inspiration for several years now. Those pictures raise a lot of interesting questions, still, about how things signify and how we find meaning in objects and images. I'm exploring how contemporary and historical print culture might fit into that conversation as well.

What caused you to gravitate toward the materials and processes you are currently using?

NG: This is a very interesting question. In my art making, it is the concept that determines my medium and not the other way around. If the concept needs drawing tools and paper that is what I'll be using. Other concepts or ideas required use of dried paint, pin or nails and those were the mediums that I had used. But for the time being different types of papers, inks and drawing pens are what works well for the type of drawings that I make. I might make a painting in the future if the concept requires use of paint and canvas instead of drawing mediums.

EK: I'm part of the last generation that remembers a time before the Internet. Until I was nearly an adult, books and printed matter were still one of the primary mediums for encountering new ideas. Print may or may not be dead, but it's inarguable that its role has changed. Some may want to eulogize, but I think this shifting landscape is an amazing place to play. What is print now? What can it be? These are really exciting questions to me, and they keep me working in the field of print.

Current Work

The following questions are intended to offer insight into the artist’s current work and what they intend their audience to understand.

What role does process have in your work?

NG: In the writing-drawings that I do, critical thinking that comes before the process has a greater role. Since I use a specific written language (Farsi) to make art, the repetitive lines of phrases that unfold into forms or images need to make sense. I tend to spend a lot of time into thinking about the relationship in between the meaning and the importance of the phrases and the possible images that they can create on paper. In other words, the images need to respond to the phrases and vice versa. Also the titles of my drawings are the translations of the phrases that have been written in them. Due to this I need to make sure that the translation is not only true to the actual meaning of the words, but also they can carry the same sensibility into the image. The actual process of writing-drawing could sometimes be meditative but not always. In some of my drawings I have to rotate the paper in order to write in a specific direction or pattern. While working on larger drawings I walk around the table and change position in order to be able to work on different areas on the paper. It is a time consuming and labor-intensive process and I cannot make any mistakes. Ink is not a forgiving medium and in case of any mistakes, I have to start over and make the same drawing again.

EK: As a printmaker, it's pretty much impossible to make work that isn't in some way "process oriented." It can be very seductive. Dangerously so, I think. I'm trying lately not to go too deep in this direction because eventually you're just talking to other printmakers. Or worse, talking to yourself. I want to figure out how a process can communicate to someone who may not already be ensconced in it without at the same time losing what makes that process unique. It's tricky.

How do you know when a piece is complete?

NG: I don't over work my drawings and at a certain point I stop working on them. After a day or two I go back to them with fresh eyes. This is usually when the work/s decides if they need more attention or if they are complete. I would say that knowing when to stop is intuitive.

EK: In printmaking, there's often a point of no return, when you have to commit to an image. Once you put ink on paper, there's often no going back. So I have a decent-sized collection of things that are complete and things that are complete and utter failures. Often, when things go badly, I feel like an idea or image just wasn't ready yet, and I find that the really good ideas eventually bubble back up to the surface, sometimes years later, more fully formed.

What is the one idea/thought you hope people will have/take away with them after viewing your work?

NG: It is challenging not to be able to read a foreign language in works of art. One might feel like being stopped and frustrated at the entry point. My hope is that the viewers can find beauty in what they see before trying to figure out what is the meaning of the written text. I would like for the viewers to understand that I could paint or actually draw the objects or shapes with paint or ink instead of re-creating them with written words. Writing the phrases in my mother tongue not only connects me with my roots but also depicts the limitations of translation. Perhaps I need to give life to the phrases by accompanying them with imagery to express myself fully. And lastly, I hope that the curiosity and questions that might follow viewing the drawings could open up a conversation on the themes of un-known and un-familiar and specifically Persian Culture.

EK: I'm more interested in generating conversations than giving lectures, especially since some of my themes, like environmental justice and humanity's place in the natural world, can be polarizing. The biggest idea I hope to convey in my work is that although we will inevitably fail to uncover final, fixed truths, active inquiry and the pursuit of knowledge remain essential to human life. No one has all the answers, but it's imperative we look for them anyway.

Why do you create art?

NG: I create art because it is the only way that I can express myself. Art is the only language that I know to communicate with the world around me. It is like breathing to me.

EK: I want to talk to people. Some of them are the authors I've read. Some are people I'll never meet. Some may be looking at my prints, right now. Art is thinking out loud.

What role does the artist have in society? Why do you think art is important to society?

NG: I don’t think that our civilizations would be where it is today without the creative minds of artists and designers. Our museums are filled with what artists have been creating. Makers and designers of functional objects influence how we live, dress and decorate our homes. Art is about our experiences, memories, how we think and reflect upon our societies. Art has the ability to challenge us on the issues that are not easy to talk about like politics, religion, gender, sexuality and so many other topics. Art can also make us pause and think.

EK: Art isn't going to save the world, at least not on it's own, but I believe artists can model better relationships through their work, pointing towards a better world. It's important to keep trying to save the world, and artists have always had a part to play. Sometimes it's making the posters and banners to be carried through the streets, other times it's just making the stuff that makes life more bearable. Sometimes I make topical work, sometimes I make pictures of flowers.

Why do you think it’s important to support the arts?

NG: Not supporting art is just like not eating food. Art is vital to our civilization. If our societies stopped supporting art and artists where would we go to find beauty? How would we satisfy our hunger for great music or play? Art does not only promote critical thinking, but it also records our history for the generation to come.

EK: See my previous answer re: saving the world.